By Alisdair Blackman

Originally published on Switzer Daily

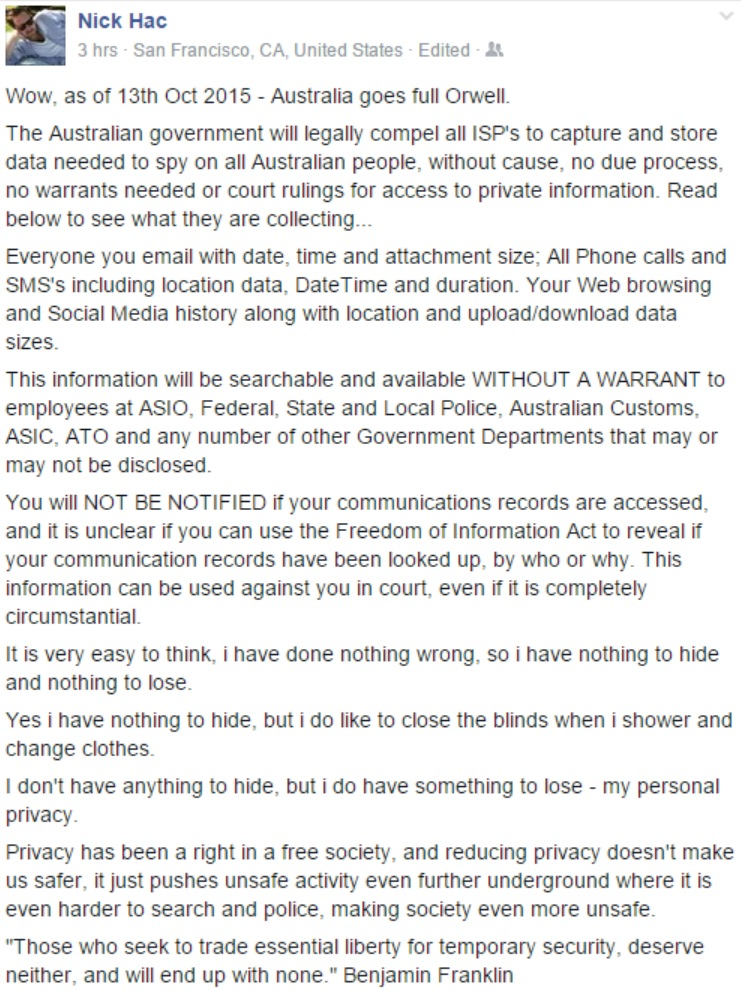

On 13 October 2015, Australia’s mandatory data retention scheme quietly came into force – ushering in one of the most sweeping surveillance reforms in the country’s history. Yet, despite its profound implications, public awareness and scrutiny remained alarmingly low.

Inspired by Nick Holmes à Court’s impassioned Facebook post, I began digging deeper.

What I found was troubling: only a handful of articles addressed the scale and scope of this change. One of the most illuminating came from respected journalist Quentin Dempster, who laid bare what the government would – and wouldn’t – collect from your internet service provider.

What the Government Can Access

From 13 October 2015, Australian authorities gained warrantless access to a wide array of metadata, including:

Emails

- Who you emailed

- When you sent it

- Attachment sizes

Phone & SMS

- Numbers you called or messaged

- Missed calls

- Time, date, and duration of communications

- Your approximate location during calls or texts

Online Activity

- Your IP address

- Time and duration of web sessions

- Upload/download volumes

- Potentially your browsing history (if retained by your provider)

Location Data

- Geographical data tied to your communications

In short, the government can now know who you’re speaking with, when, where, and how often—without needing a warrant.

Who Has Access?

The list of agencies empowered to access this data is extensive and includes:

- ASIO

- AFP

- State and territory police

- ACCC, ASIC, Customs, and Border Protection

- ICACs and Crime Commissions across multiple states

- Any other agency the Attorney-General designates

And if telcos or ISPs resist? They face penalties of up to $2 million for non-compliance.

The Risks We’re Not Talking About

Beyond civil liberties, there’s a glaring issue: data security. This trove of metadata is a goldmine for hackers. What safeguards are in place? Who’s accountable if it’s breached?

Between 2013–2014 alone, over 330,000 metadata requests were made in Australia. That number will only grow under the new regime.

As Baker & McKenzie’s Patrick Fair told Fairfax Media, metadata can be accessed without your knowledge—and used against you in court.

Where Is Our Recourse?

Greens Senator Scott Ludlam captured the sentiment best:

“This is a bill to entrench a system of passive mass surveillance. It is corrosive of the very freedoms that governments are elected to protect, and it has no place in a democracy.”

Earlier this year, over 10,000 Australians had their personal details handed to Dallas Buyers Club LLC to pursue copyright infringement claims. If rights holders can demand our data, where is our right to privacy? Where is our recourse?

We are the rightful owners of our personal data. And yet, we seem to have surrendered it—quietly, passively, and without protest.